Week 3: Volume III, Chapter 1 - Quantum Behavior

I realized that I am fairly familiar with the conclusions and consequences of quantum mechanics, but a bit uninformed of the mathematics, so this week I read Feynman's first chapter on quantum mechanics to gain an appreciation for the underlying theory (which, ironically I won't cover in much detail here). I will likely continue this trend in the coming weeks by diving deeper into the field. Feynman presents this material by describing an experiment with bullets, an experiment with water, and an experiment with subatomic particles (electrons, protons, photons, etc). You will often hear folks say that an electron (or other subatmoic particle) is a particle and a wave. This is not exactly true however, and Feynman hammers this home. He continuoously harps on the fact that subatomic particles, although they sometimes behave like a wave or sometimes behave like a particle, are in fact neither a wave nor a particle. The chapter outlines the double slit experiment and how we expect bullets, water waves, and subatomic particles to each behave in this experiment. For those of you who may be unfamiliar with the double slit experiment, imagine two walls. The first wall has two slits in it and the second wall is solid. That's actually really all you need to know for now.

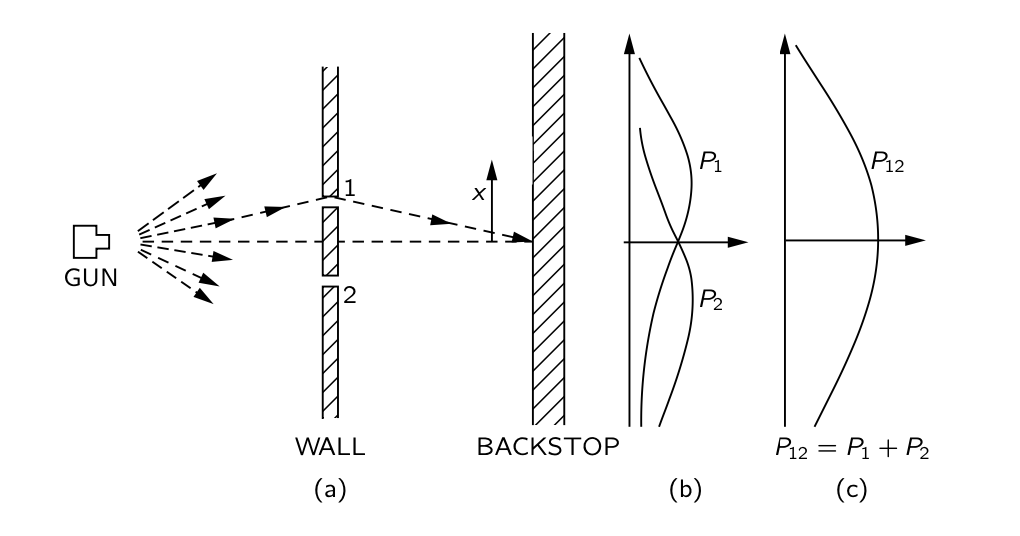

An Experiment with BulletsThe first experiment uses the two walls described above and fires bullets randomly at the first wall. The bullets are able to bounce off the edges of the slits in the first wall if their trajectory so takes them on that path. Now, imagine we cover up hole 2 and fire our gun randomly. It stands to reason that the probability curve describing where the bullets end up is P1 as seen in Figure 1. The maximum point of this curve is on a direct line from the gun to hole 1. We repeat this exercise while covering hole 1 and, as expected, we observe P2 as the distribution of bullets on the back wall. Now, if we leave both holes open, it should be intuitive that the bullets arrive at the back wall following a distribution P12=P1+P2.

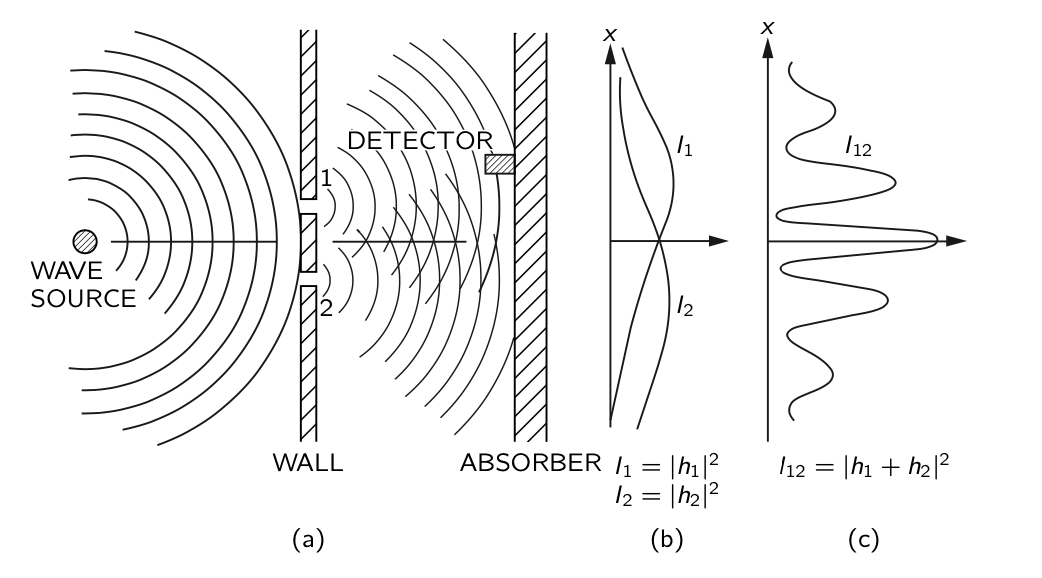

Imagine now that our two walls are in a shallow pool and where the gun used to be there is now a motor oscillating up and down creating concentric waves. Instead of counting how many bullets arrived at each spot on the back wall, we will measure the intensity of the wave at each point along the wall. Remember that waves interfere with each other both constructively and destructively, this will be crucial to our understanding. Similarly to the experiment with bullets, we now cover hole 2 and observe the intensity of the wave at the back wall and record it. We do the same for hole 1 and we observe wave intensity distributions I1 and I2 as seen in Figure 2. Next, we uncover both holes and again record the intensity at the back wall. However, different than the bullets, the wave simultaneously passes through both holes creating two different waves that interact with one another between the front and back wall before reaching the back wall. This results in the wave intensity distribution I12 which is not described by the sum of I1 and I2. With that being said, it is not difficult to describe mathematically I12 in terms of I1 and I2. I won't show it here though because the point is that although the results at the back wall are the same between bullets and waves when we cover one hole, the results are different when both holes are left open.

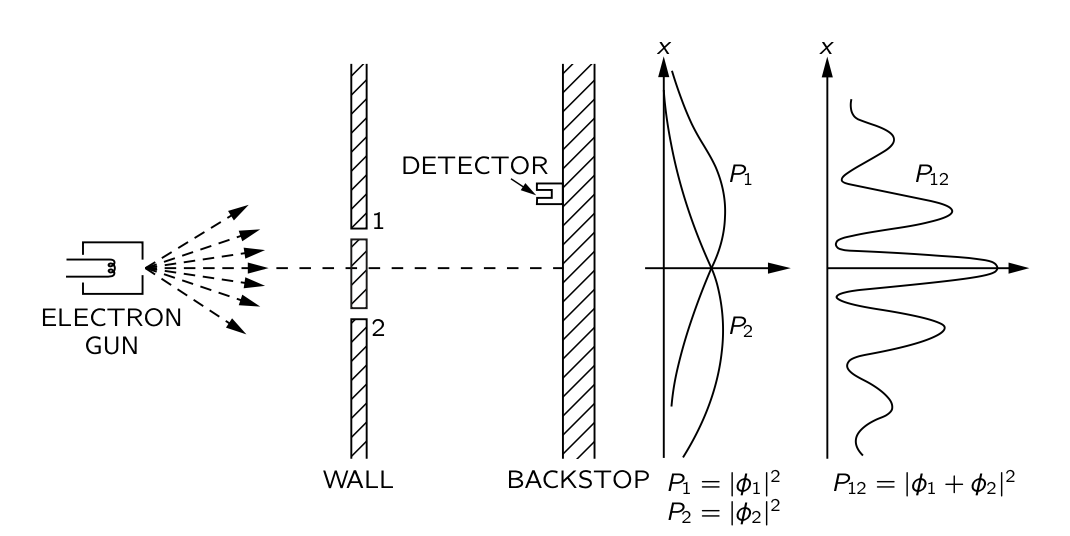

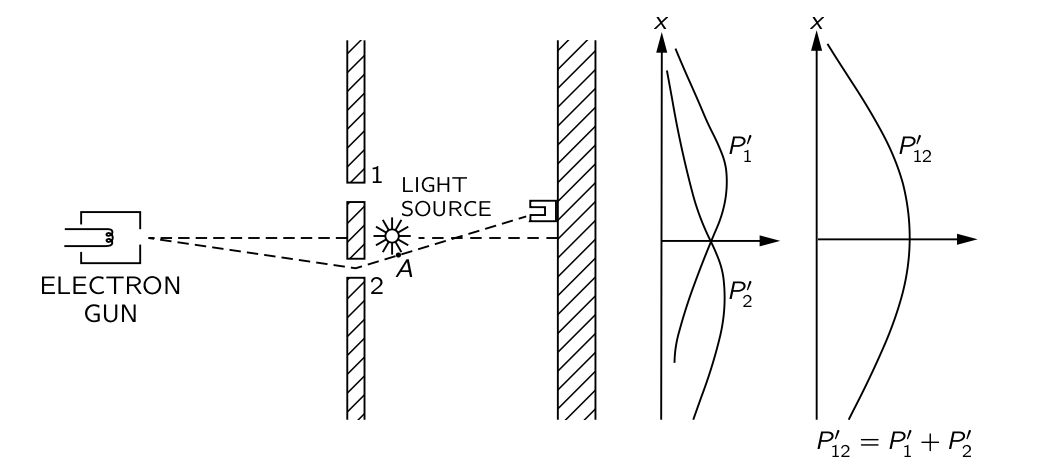

Finally, we now understand how particles (bullets in our case) and waves behave when subjected to the double slit experiment. Now, we would like to know if electrons and other subatomic particles are particles or waves. To detect an electron we can use a Geiger Counter. This device will produce an audible clicking sound when an electron hits it. It should be noted that the device either clicks or doesn't click. There are no "half-clicks." So, we go ahead and assemble an electron gun and begin to fire it randomly at the wall. First, we cover hole 1 and then hole 2 to record our probability distributions of inbound electrons at the back wall by listening for clicks by the Geiger counter. These two distributions look exactly as they did in the case of bullets and waves, but it appears the electrons are arriving as individual particles since we are hearing clicks from the Geiger counter. We then open both holes and observe the distribution of electrons at the back wall and find that it looks like P12 in Figure 3 below. Indeed, this is how electrons behave in this experiment. We are left a bit stumped because the Geiger counter makes it seem that electrons are particles, but the distribution at the back wall makes it seem as if electrons are waves. Maybe the electrons are particles and the distribution observed on the back wall can be explained in some manner other than by saying electrons are waves. We will make the following proposition: because the Geiger counter shows that electrons are particles, that must mean that each electron passes through only slit 1 or slit 2, not both as a wave does. In order to confirm this we will set up a device (labeled "light source" in Figure 4) to detect electrons and determine which slit they passed through. When we do this, something extremely strange happens and to this day, no one knows why. The result is shown in Figure 4. As soon as we observe the electrons at the slits, the distribution at the back wall follows a pattern in-line with what we would expect for a particle. When we do not observe them at the slits, the pattern at the back wall is what we would expect from a wave. In this sense, electrons are neither waves nor particles. This is where the common term "wave-particle duality" comes from.